Parish: RINGSFIELD

District Council: EAST SUFFOLK (previously Waveney)

TM 401 859

Plant nursery and gardens open to the public on specific days during the summer

Situated c. 6.5km (4mls) south-west of Beccles and 8km (5mls) north of Halesworth, early-nineteenth century Redisham Hall (Grade II) is c. 25m (80ft) above sea level beside a tributary of the Hundred River that flows eastwards towards the North Sea. The house stands within its gently-undulating early-nineteenth century landscape park in a rural location on predominantly clay soils, west of the road between Redisham village and Ringsfield to the north.

Redisham originally comprised two villages, Little Redisham and to the south Great Redisham. The lost settlement of Little Redisham is believed to have been close to the parish church of St James, its ruins now within the boundaries of Redisham Hall Park and north of the house. The original church or free chapel was a small building without aisles and tower and probably fell into disrepair after the benefice was annexed to the Rectory of Ringsfield in 1450. It is said to have been in ruins in 1613. What remains are only fragments of the walls and the site is now covered with trees. Little Redisham and most of today’s Redisham Park were incorporated into Ringsfield parish during the early-seventeenth century.

OWNERS OF REDISHAM HALL

The Garney family held the Little Redisham Hall manor from the fifteenth century and Nicholas Garney, High Sheriff for Suffolk, built the original Elizabethan Little Redisham Hall. The estate passed to the Duke family, once of Brampton and with their main home at Benhall near Saxmundham. The Hall is shown to have been occupied by Revd D. Tanner on Hodskinson’s 1783 map.

In 1820 the estate was bought by John Garden Esq., who built the present house on a slightly different site three years later. Its name was subsequently changed simply to Redisham Hall. It passed down the Garden family and became the home of American born Princess Caroline Murat (b. 1833), the great niece of Napoleon Bonaparte and granddaughter of Joachim Murat, King of Naples, after her marriage to John Lewis Garden. John died in 1892 and his widow stayed at Redisham until her death ten years later when Thomas de la Garde Grissell J.P. (b. 1852) made Redisham Hall his home, although it is unclear if he inherited or bought the property.

On Thomas’ death on Christmas Day in 1915 it passed to Cecil Henry Grissell and Frank de la Garde Grissell. Two years later the estate was for sale at the direction of Capt. Thomas de la Garde Grissell, although only part, including the agricultural portions, sold. Thomas was the son of Thomas Grissell of Norbury Park in Surrey, a building contractor and cousin and partner of Samuel Moreton Peto of Somerleyton Hall c. 16km (10mls) to the north-east, who were well-known railway contractors.

The whole estate, including the house standing in 81ha (200a) of parkland, was for sale once more in 1925, and bought by W. W. Yates, Esq. However, within five years it was on the market again after his death. The sales particulars make reference to the Hall, stables, pleasure grounds, walled fruit and vegetable gardens, glasshouses, outbuildings, lodge house and four cottages, one being tenanted by the gardener, Mr Clarke. Ownership passed to two further people, Colonel Mortimer from 1930 to 1937 and Captain Dowling 1938 to 1940, before being bought by Geoffrey Palgrave-Brown who began a careful restoration of house and gardens that was necessary after being occupied by the army during World War II. The estate was put for sale in 1955 when the sales particulars described it as a ‘Particularly fine agricultural, residential and sporting estate’, but presumably did not sell and is today owned by the Palgrave-Brown family trust.

REDISHAM HALL

The Gurney’s sixteenth century house is shown on Hodkinson’s 1783 map on a site slightly south-west of the present house and had a small area of gardens and pleasures grounds but no park. It was demolished by John Garden in 1820 and today’s Redisham Hall was completed in 1823. Described in 1846 as an elegant residence, the Regency house was considerably enlarged and refaced by John Lewis Garden c. 1880. It was further enlarged for Thomas de la Garde Grissell c. 1904 with the addition of a ballroom to the south-east and a south-west-facing garden terrace. The twentieth century saw further alterations including an entrance porch at the beginning of the century.

The various outbuildings to the south of the present house, including the red brick coachman’s house with curved floor plan and single storey range of stabling are attached to a partly-walled garden. This garden has eighteenth century, if not earlier, elements and may be related to enclosures associated with the original Elizabethan house.

REDISHAM PARK

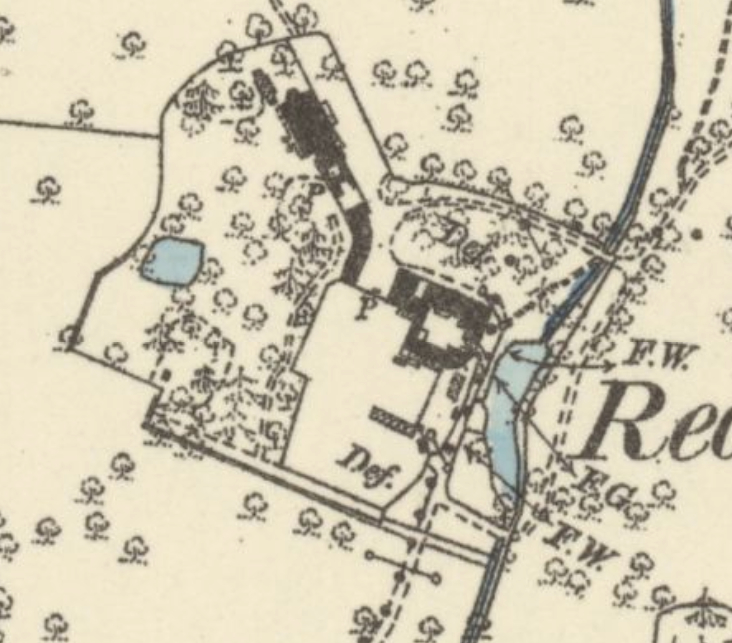

The park was newly-created in the early-nineteenth century, almost certainly by John Garden when he built his new house. At the time of 1844 tithe map the park was slightly smaller than today and sub-divided, which would have helped for grazing management. By 1883 the park had been extended northward to include the ruinous church and site of the lost settlement of Little Redisham. Belts of trees surrounded the north-east and northern park boundaries and hedgerow trees, dominated by oak, and ancient woodland such as Great and Briery Woods, were incorporated in this perimeter belt.

There were two entrances into the park that are in use today. The entrance to the north, its drive flanked by plantings mainly of horse chestnut, runs approximately beside the river and passes the site of the ruined church and lost settlement before arriving at the Hall. Today this is a public bridleway that appears to be the route of the ancient road connecting Ringsfield via Little Redisham village and the Elizabethan Little Redisham Hall and onwards towards Ilketshall St Lawrence and the roman road called Stone Street. During the early-twentieth century this drive had an entrance lodge, which has since been lost and replaced by clumps of deciduous trees on either side of the drive. Some freestanding additional trees have been planted along its route.

The other entrance is from the east and is used by visitors to the site today. Its drive is quite direct and formal, passing through parkland dotted mostly with oak trees. Between 1883 and 1906 an avenue of trees was planted to line this drive, probably by John Lewis Garden. It crosses a red-brick ornamental bridge over the river before arriving north of the house. A surviving lodge at the east entrance to the park is not marked on maps until the middle of the twentieth century. Most of the length of the drives has metal fencing to separate them from the parkland and grazing animals, much of it is original, restored or new to match.

Today this medium sized park is well-preserved. It covers c. 90ha (220a) including its pleasure and walled gardens. Some typical nineteenth century ornamental parkland trees such as lime and cedar of Lebanon are retained, although some areas appear to have incorporated existing hedgerow standards. More recently a new woodland and wildflower garden has been established north of the house.

THE PLEASURE GARDENS

Today the 2.02ha (5a) formal gardens to the west and south of the house include lawns, herbaceous borders, shrubberies, ponds and a brick-lined ha-ha constructed of eighteenth century bricks. This curves around the house from the north to the west and south, separating the pleasure gardens from the parkland beyond. It is shown on the tithe map of 1844 and possibly has origins dating back to the layout of the older house and gardens. During the twentieth century a square nineteenth century pond south of the house was developed into a series of linked ponds with a small cascade and fountain. To the north-west of the house a late-nineteenth century lozenge-shaped orangery that is shown on the 1883 OS map was lost by the 1920s. Today the 1904 garden terrace gives attractive views across lawns to shrubberies, the ponds and the parkland beyond.

THE KITCHEN GARDEN

A productive partly-walled kitchen garden covering c. 0.8 ha (2a) lies south-east of the house and is attached to what were once farm buildings to the south of the stable yard. The tithe map of 1844 shows an area of kitchen gardens but with only an eastern wall that curves at its southern end where it joins further farm buildings. This wall is constructed of eighteenth century, or possibly earlier, bricks suggesting they were part of former enclosures associated with the older house. An additional wall was added between 1844 and 1883 slightly further west to create a narrow walled enclosure. There is a surviving nineteenth century sunken freestanding ridge glasshouse towards its northern end that would have been used for both flower and vegetable propagation. The 1883 OS map shows a larger kitchen garden enclosure west of this, although this appears never to have been enclosed by brick walls but by a beech hedge that is mentioned in sales particulars of 1930. By 1883 there were lean-to glasshouses against the original northern farm buildings used for peach and carnation cultivation plus a freestanding vinery glasshouse further south.

This larger garden enclosure was originally divided into two, the more northern section in use much earlier than that to the south. The southern trapezoid-shaped section is a later twentieth century extension to the kitchen garden, described as a ‘Yard which could readily be added to the Pleasure Grounds and formed into another Walled Garden’ in the 1930 sales particulars. This was later incorporated to form one large garden by adding a brick and flint wall to the west that was subsequently strengthened with brick buttresses, plus a hedge to south. A nineteenth century crescent-shaped pond created from the river lying east of the kitchen garden has been in-filled, although the date of this is unclear.

Today much of the southern parkland is now in arable cultivation, although most of the northern parkland has been maintained. Redisham Hall is let for country house holidays, with various other buildings on the site converted for residential and holiday accommodation. Part of the kitchen gardens is home to Redisham Hall Nurseries, an independent plant nursery that are open on set days during the summer.

SOURCES:

Beccles & Bungay Times archive dated 27 April 1940 advertising the estate on the market and listing recent owners. Information from www.foxearth.org.uk.

East Suffolk Local List, Historic Parks and Gardens, East Suffolk Council, November 2021.

Kelly’s Directory of Cambridge, Norfolk and Suffolk, 1922.

Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, Excursions, 2001.

Suckling, Alfred, The History and Antiquities of the County of Suffolk, Vol. 1, 1846.

Suffolk Gardens Trust, Walled Kitchen Gardens Recording Group, ‘Survey of Redisham Hall Kitchen Garden’, 2009 (unpublished document).

Walled Gardens of Suffolk, Suffolk Gardens Trust, 2014.

Venn, John (ed.), Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, Vol. 2, 1951.

Williamson, Tom, Suffolk’s Gardens and Parks, 2000.

White, William, Directory of Suffolk, 1844, 1874.

https://www.dorkingmuseum.org.uk/lieutenant-colonel-bernard-salway-grissell/ (accessed November 2018)

https://landedfamilies.blogspot.com/2021/ (accessed November 2018)

http://www.greatwarbritishofficers.com/index_htm_files/GRISSELL_F_Research.pdf (accessed November 2018)

East Suffolk Gazette 1917–18, accessed via https://www.foxearth.org.uk/BecclesAreaNewspapers/EastSuffolkGazette1917-1918.html also 1940. (accessed November 2018)

Census: 1851

1783 Hodskinson’s Map of Suffolk in 1783.

1844 tithe map and apportionment for Ringsfield with Little Redisham.

1883 (surveyed 1883) OS map.

1906 (revised 1903) OS map.

1928 (revised 1926) OS map.

1951 (revised 1947) OS map.

2025 Google Earth (Google Earth / Airbus, Map data © 2024)

Heritage Assets:

Suffolk HER: RGD 002, RGD 003, RGD 005, RGD 007, RGD 008, RGD 013, RGD 016.

Redisham Hall (Grade II), Historic England No 1182824.

Historic England Archive, Ref: SB00466, Sales Particulars.

Historic England, SC01004, The Redisham Hall, Suffolk, Outlying Portions Sales Particulars, 15 June 1917.

Suffolk Record Office (now Suffolk Archives):

SRO (Lowestoft) 1015, Redisham Hall estate, title deeds 1353–1911.

SRO (Lowestoft) 1025/2/2/4, Annual statements of accounts of Redisham Hall estate of John Garden, 1817–34.

SRO (Lowestoft) 947/4, Redisham Hall estate, 1862–71.

SRO (Lowestoft) 1025/2/2/14, Cover of Sales Particulars of Redisham Hall Estate, 1895.

SRO (Lowestoft) 1117/331/13, Sales Particulars, 7 August 1925.

SRO (Lowestoft) 1117/331/4, Sales Particulars, 8 May 1930.

Site ownership: Private

Study written: July 2025

Type of Study: Desktop and site visits 2009, 2018, 2024.

Written by: Tina Ranft

Amended: