(hall demolished in 1923)

Parish: GREAT AND LITTLE LIVERMERE

District Council: WEST SUFFOLK (previously St Edmundsbury)

TL 877 713

Not open to the public except on public footpaths that cross the site near to the lakes and mansion site.

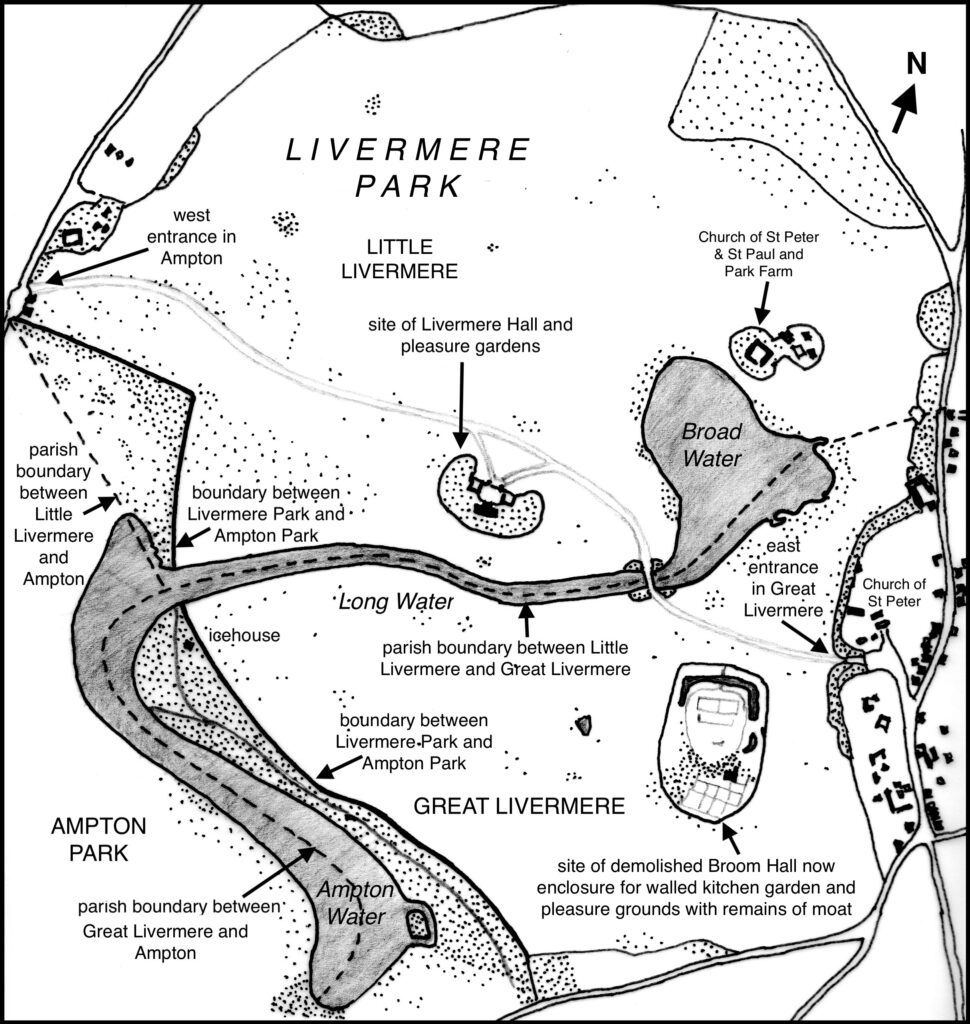

In a flat landscape in the Brecklands with its poor sandy soils, Livermere Park was created in the eighteenth century from land in both the parishes of Little Livermere and Great Livermere to surround a new Georgian mansion. The boundary between Little Livermere and Great Livermere ran through two lakes within the park, Broad Water and Long Water. Today part of original Little Livermere parish has joined with Ampton and Timworth to form a unified parish, whilst the rest is now in Great Livermere. To the west Livermere Park adjoins Ampton Park, originally following the parish boundary running centrally through Ampton Water but in the mid-eighteenth century it moved slightly eastward when Ampton Park was enlarged and a park pale created. The site of Livermere Hall, which was demolished in 1923, was in the more northern parish of Little Livermere c. 13km (8mls) north-east of Bury St Edmunds and replaced Broom Hall in Great Livermere as the main residence of the Livermere Estate, with the Broom Hall site becoming the walled kitchen garden and pleasure gardens enclosure.

OWNERS OF LIVERMERE PARK

The manor of Little Livermere was known as Murrells and was acquired by William Cooke and William Chapman in 1567. The lost medieval village of Little Livermere once stood in the northern section of the park, north-west of the thirteenth century Church of St Peter and St Paul (Grade II*), which now stands as a ruined shell. In 1573 Cooke and Chapman went on to acquire the neighbouring manor of Great Livermere, known as Broom Hall, which included a ‘mansion house, gatehouse and closes’ close to the thirteenth century Church of St Peter (Grade I), although it has been suggested that the manor of Broom Hall was owned in 1670 by the Caxton family with a Miss Caxton living in a large house there with seventeen heaths in 1674. If the account of Cooke and Chapman jointly owning the estate is correct, it was later partitioned with Broom Hall (Great Livermere) to Cooke and Murrells (Little Livermere) to Chapman. On the death of the men both holdings were inherited by Cooke’s son Richard. It stayed in the family, who eventually changed the spelling of their name to Coke, until it appears to have been sold in 1709 for £7,500 to Thomas Lee and documented as including the manors of Murrells and Broom Hall, messuages, two dove houses, six gardens and the same number of orchards, arable land, pasture and meadow, plus a large area of heath, all amounting to c. 850ha (2,100a). Thomas’s family were established landowners in Lawshall near Bury St Edmunds and Thomas continued the landholding tradition when he acquired further property in Great Livermere in 1715 to add to his estate.

Thomas’s son Baptist Lee owned Livermere from the early 1720s until his death in 1768. His winnings of £30,000 in the state lottery in 1733 allowing him to make substantial improvements to his Livermere estate. After his death it was inherited by his nephew Nathaniel Lee Acton (d. 1836) of Bramford and passed, first to his elder sister and then on her death to Harriet his younger sister, the widow of Sir William Fowle Middleton, 1st Bart, before passing to the 2nd Bart, also William Fowle Middleton (d. 1860). Without heirs it passed from William to his nephew Sir George Nathaniel Broke who assumed the name Middleton and then to his niece Jane Anna who married the fourth Baron de Saumarez.

One of the many estates that had descended to the family in Suffolk, Livermere stayed in the de Saumarez family, although their home was Shrublands in Barham, until the early twentieth century. During this time it was leased out to various tenants. It appears to have been used in World War I by the army and in 1919 Livermere Park was sold to Pierce Lacy (later Sir) of Ampton Hall. Pierce was obviously more interested in expanding his landholding than the mansion because it was demolished four years later. During World War II an army camp was established on the estate and later it was turned over to farming, which continues in the 2020s by the Turner family of Ampton Hall.

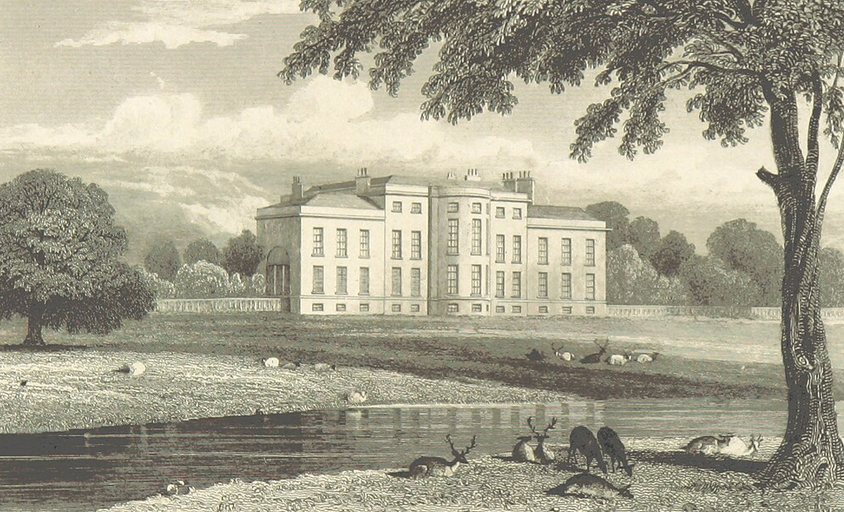

LIVERMERE HALL

Although said to have been newly-built by Baptist Lee in c. 1720s, it has been suggested that stylistically the central core of the mansion was more in keeping with the second half of the seventeenth century, a period when it was owned by the Coke family. A painting of the mansion dated c. 1730 and attributed to Peter Tillemans shows the north-facing entrance front of the building with central core and two large wings to either side of an entrance courtyard. This is enclosed by a scalloped-shaped wall topped with iron railings and ornate metal entrance gates, all surrounded by a ha-ha. Baptist Lee probably added the wings to house, stabling and offices when he became the owner and established his landscape park during the 1720s.

In the late 1790s Nathaniel Lee Acton made changes to the mansion, some attributed to the architect Samuel Wyatt. This included alterations to the front of the central core and opening-up the entrance courtyard. Further bays with south-facing windows were added to the sides of the core with the use of mathematical tiles on the exterior. A few minor changes were made to the mansion during Nathaniel’s life but after that it remained unaltered during the period leading up to World War I and its final demolition in 1923. Today the site is marked by an area of rough shrubland.

THE PARK

Livermere Park was said by J. Whitaker in his book Deer Parks and Paddocks of England published in 1892 to have been created from the remains of a medieval deer park. It is believed the landscape park was established c. 1728 by Baptist Lee from the consolidated landholdings acquired by his father Thomas from 1709 to 1715 in both Little and Great Livermere. Divided by the waters of Broad Water and Long Water, it seems likely that the landscape park was viewed with hunting and fishing in mind as much as the visual effect and social status it gave its creator. The medieval village of Little Livermere is believed to have been moved out of the park by Baptist between 1735 and 1750, although it has been suggested that, due to the poor soils, the village may have been depopulating long before the landscape park was created. The village was located near to the remains of the parish church and seventeenth century Park Farm (Grade II) and is shown on historic aerial photographs where earthworks of a street with tofts on either side can be seen, although after conversion of the park to arable in the 1960s only slight soilmarks survived. With the building of the new mansion in Little Livermere, the site of the old Broom Hall in Great Livermere became pleasure grounds and a walled kitchen garden. William Kent is believed to have worked on these pleasure gardens and it is likely he had a hand in designs for landscaping the park soon after the mansion was built.

The painting attributed to Peter Tillemans dated c. 1730 depicts the mansion in its grounds with clumps of trees on either side of the wings of the building, open parkland to the north with an avenue running due south on the central axis of the house. Nearest to the house the trees are mature but those further south newly-planted. It is difficult to assess how much of the scene was a reality rather than an idealized landscape for a property of this status, particularly as the avenue would have crossed one of the meres within the park where there is no obvious bridging point. No avenue or remnants of an earlier avenue are shown on Hodskinson’s 1783 map, nor on later maps, suggesting this element of the landscape was a proposal that was never implemented because avenues became unfashionable during the following period.

With his neighbour James Calthorpe, Esq. of Ampton Hall, in 1753 Baptist agreed to create a park pale between their two properties. Parts of an earthwork bank and ditch still survive that have been assessed by Historic England as partly dating back to the medieval deer park that may have been enlarged at this time. They also joined forces to enlarge the existing meres by damming them to form the surviving linked Long Water and Ampton Water, including a wooden bridge. By 1771 a number of trees had been planted, including 16,000 oak, ash, elm, sweet and horse chestnut and beech, plus Norfolk willows, Turin poplars and sycamores. Three years later 1,700 Scots pines were added in various plantations throughout the park. Hodskinson’s 1783 map shows the park and lakes, mansion north of the central lake and the moated site of the old Broom Hall developed into kitchen and pleasure gardens.

Commissioned by Nathaniel Lee Acton, in 1790 Humphry Repton surveyed the park and in the following year produced one of his famous Red Books in which he suggested a number of alterations and additions to the park and the pleasure grounds surrounding of the Hall. He felt the wings of the mansion were out of proportion to its central core and that new trees should be added to those existing on either side to create a more balanced and ‘harmonious’ structure, with further trees north of the mansion to screen the arable fields beyond. He also suggested the western shrubbery should be opened up to allow views to trees further west. Within the wider park he proposed alterations to both Little Livermere church and Great Livermere church, which lay just outside the park boundary. To give a less marsh-like look he wanted Broad Water dredged and the spoil used to create islands and Long Water widened. Along their shores, plantations were to be added and the existing boathouse altered to look like a chapel or church. New walks, approaches and entrances were also suggested, although Repton was impressed with the ‘beautiful scenery’ that surrounded the pleasure garden south of Long Water but wanted a new path to it with ornamental planting and the orchard was to be fully enclosed by a wall. As was often the case with Repton’s landscape proposals, it is unclear how many were actually implemented, although a map dated c. 1815 shows a few clumps of trees, an island created in Broad Water with a new bridge and a lodge built at the western entrance in Ampton. Repton’s Red Book for Livermere was deposited with Suffolk Records Office in 2008.

At the same time as the London nurseryman Lewis Kennedy was making proposals for neighbouring Ampton Park, in 1815 Nathaniel commissioned him to produce plans for further landscaping at Livermere. Known mainly for his picturesque designs, Lewis approved of the existing trees within the park, describing them as having ‘grown venerable’ in suitably elegant large groupings, but suggested that the east entrance in Great Livermere village was ‘altogether unworthy of the ostensibly tasteful, and elegant style’ of the mansion itself. He provided a picture of how he felt it should look with plantations beside it as well as more planting along the east drive to enhance that approach to the Hall. He also proposed new plantations around the lakes with existing clumps of trees thinned out to give better views from the house and the island enlarged and planted with quick growing trees.

In 1823 the house was described by John Neale in his Views of the Seats of the Noblemen and Gentlemen as in a ‘large and beautiful park’ with a ‘noble serpentine river formed [between Livermere and Ampton Park] which winds through thick planted wood, with very bold shore, in some places wide, in others so narrow that the overhanging trees join their branches and darken the scene, having a charming effect’. Uneven and wild banks of the water combined with a ‘fine green lawn in gentle swells’ were described and deer and cows browsed within the park.

The tithe map (surveyed 1840) associated with the 1847 tithe apportionment for Little Livermere shows the parkland with a large plantation on the north-east boundary that is named ‘The New Wood’ on the apportionment. Further west along the park boundary was an area called ‘New Spinney’. To the west of the mansion there was a triangular area that formed part of Ampton Park with surrounding park pale separating the parks that was shielded from the view from the mansion by a further plantation. Clumps of trees were scattered around the park but predominantly near the drive. This had two lodges at the entrance in Ampton village to the west, both survive although the northern lodge has been substantially enlarged.

The drive swept through the park in front of the mansion and continued to a bridge across Long Water at the parish boundary. Clumps of trees, much as Kennedy had suggested, surrounded the edges of Broad Water and nearby the church and farm complex were surrounded by trees. In the same year the tithe map for Great Livermere was produced. Along the western boundary of Livermere Park it showed Ampton Water shielded from view by a long and narrow plantation. The drive in the northern parkland continued south-east over a bridge flanked by clumps of trees, passing the kitchen and pleasure gardens to the Great Livermere village entrance, with two lodges that survive today. A few trees were dotted around the southern parkland, some beside the drive as suggested by Kennedy.

Little change took place in the park between 1840 and the production of the 1883 OS map, although tree planting appears to have become much denser with additional small plantations, more clumps and numerous freestanding trees in both the northern and southern park areas. Two boat houses are shown on the 1883 map, one in front of the house and the other at the junction of Long Water and Ampton Water.

No substantial change took place until the second half of the twentieth century when the parkland was converted to farmland. It became an open landscape of mixed farming, mostly devoid of trees except those along the banks of Long Water. The lakes and three woods known as Samson’s Plantation to the north-east, Three Corner Covert on the north-west boundary and Oldbroom Planation beside Ampton Water survive.

In 1823 the pleasure gardens surrounding the mansion were said to have two small flower gardens enclosing a glasshouse, exotics house and adjoining fruitery that contained ‘a very choice collection of rare plants’. There is insufficient detail on the later tithe map (surveyed 1840) that only gives a general impression of a small kidney-bean-shaped enclosure of pleasure grounds wrapping around the mansion. This consisted of shrubs and trees with some winding paths, but no other structures. It seems likely that the outer boundary of the enclosure was marked by a ha-ha. By 1883 there was a raised formal garden immediately to the south of the mansion with some open views of the water over a lawn and free-standing trees towards the enclosure’s boundary.

A photograph dated 1900 in the Spanton Jarman Collection shows the south elevation of Livermere Hall flanked by clumps of trees with a small area of formal gardens immediately in front of the house and crochet lawn in the foreground. There was dense planting to the east and west with a winding path on either side running through shrubberies and trees. That to the west was more complicated with a series of paths, some leading to a round pond, an area that may have been the site of the flower gardens and glasshouses mentioned in 1823. There was little change in the gardens until the house was demolished in 1923 after this the gardens were left to become an area of rough shrubland surrounded by fields that can be seen today.

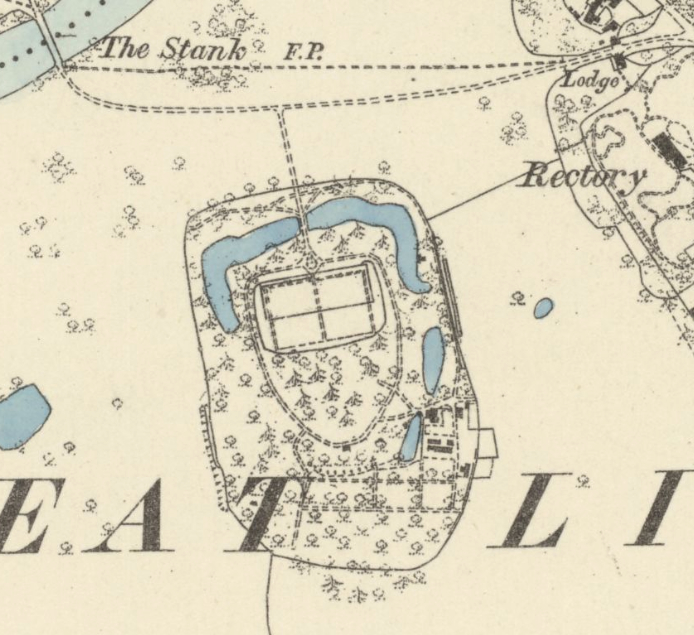

SOUTHERN PLEASURE GARDENS AND WALLED GARDEN

The kitchen garden and pleasure grounds in the southern parkland were said to extend to 6ha (15a) and originally designed by William Kent, probably soon after the building of the new mansion in 1720 and at a similar time to him working at Holkham Hall in Norfolk. This oval-shaped garden enclosure was created on the site of the demolished moated Broom Hall, which is shown on an early-eighteenth century map in the north-east corner of the moat. In 1823 the site was described as housing the gardener’s cottage and walls for fruit trees.

Shielded from the parkland by planting, in 1840 the remains of three sides of the moat survived surrounding a rectangular walled kitchen garden and pleasure grounds. The northern arm of the moat was bridged to give access from the main drive where the entrance gave views across Broad Water to Little Livermere church. To the south of the walled garden there was a lawned area that gave way to a bank of trees and shrubs shielding views to a further ‘secret’ garden with cross-paths that formed the pleasure gardens. Little changed over the following decades, although by 1883 the garden layout appears to have been simplified with less paths and denser planting to areas outside of the walled garden. In the south-east corner of the enclosure was the head gardener’s cottage. Accounts for the garden in 1899 list eight other gardeners working in 5.6ha (14a) of kitchen gardens, including 0.6ha (1.5a) of water, with 4.45ha (11a) of pleasure gardens and the gardener’s house. This appears to relate to the combined pleasure gardens of the mansion and the southern garden enclosure. The 1905 OS map shows a lean-to glasshouse against the north wall, although it seems unlikely that glasshouse cultivation was not taking place at an earlier date.

Cultivation in the kitchen garden continued well into the twentieth century. At the time of the sale in 1919 it had a vegetable garden, orchard, peach house plus one other glasshouse and summer house. Once the mansion had been demolished the gardens began to slowly fall out of use. By the early 2000s the remains of the moat and the gardener’s cottage had survived, while the kitchen garden was uncultivated and its walls degrading. Planting on the site was overgrown leaving the evidence of their previous grandeur in features such as lines of pollarded beech trees marking long-gone pleasure garden compartments.

SOURCES:

Cromwell, Thomas, K., Excursions in the County of Suffolk, Vol. 1, 1818–1819.

Copinger, W. A., The Manors of Suffolk: The Hundreds of Babergh and Blackbourn, Vol. 1, 1905.

Kennedy, Lewis, ‘Notitiae on Livermere Park, House and Gardens’, 1815, Shrubland Hall archives. Information in Williamson, Tom, Suffolk’s Gardens & Parks.

Neale, John, Preston, Views of the Seats of the Noblemen and Gentlemen in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, Vol. 6, 1823.

Page, Augustus, Supplement to the Suffolk Traveller [of J. Kirby] or Topographical and Genealogical Collections, Concerning That County, 1844.

Roberts, W. M., Lost Country Houses of Suffolk, 2010.

Suffolk Gardens Trust, Walled Kitchen Gardens Recording Group report, ‘Livermere Park, Great Livermere’, October 2011, unpublished document.

Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, Excursions 2016.

Williamson, Tom, Suffolk’s Gardens and Parks, 2000.

Whitaker, J., Deer Parks and Paddocks of England, 1892.

1736 Kirby’s Map of Suffolk.

1783 Hodskinson’s Map of Suffolk in 1783.

1847 (surveyed 1840) tithe maps and apportionments for Great and Little Livermere.

1883 (surveyed 1882 to 1883) OS map.

1905 (revised 1903) OS map.

1952 (revised 1950) OS map.

2023 Google aerial map (Imagery © Bluesky, CNES / Airbus, Getmapping plc, Infoterra Lts & Bluesky, Maxar Technologies, Map data © 2023).

Heritage Assets:

Suffolk Historic Environment Record (SHER): AMP 003, LMG 008, LMG 009, LMG 021, LMG 014, LMG 021, LML 003, LML 009, LML 014, LML 015, LML 016

Church of St Peter and St Paul (Grade II*). Historic England No: 1031249.

Church of St Peter (Grade I). Historic England No: 1283741.

Park Farmhouse (Grade II). Historic England No: 1283713.

Historic England Research Records, Hob Uid: 382790, NGR: TL 87800 71800.

Historic England Research Records Hob Uid: 382793, NGR: TL 87500 71400.

Suffolk Record Office (now Suffolk Archives):

SRO, HA93 Saumarez Family Archive, various dates.

SRO (Ipswich) HA93/2/806, Final Accord dated 11 October 1709.

SRO (Ipswich) HA93: 146881, copy of Humphrey Repton’s Red Book for Livermere Park, 1791.

SRO (Bury St Edmunds) HD526/95/9 and 13, Sales Particulars, 1919.

SRO (Bury St Edmunds) K997/54/10 and 11, Photographs of soldiers at Livermere from the Walton Burrell Archive, 1914.

SRO (Bury St Edmunds) M 592/1. Plan of Livermere (Army) Camp showing foul water drainage arrangements, June 1941.

Site ownership: Private

Study written: September 2025

Type of Study: Desktop

Written by: Tina Ranft

Amended: