Parish: NORTON

District Council: MID SUFFOLK

TL 952 666

Not open to the public

In an area of gently rolling upland clay, Little Haugh Hall (Grade II) lies in the parish of Norton c. 14.5km (9mls) east of Bury St Edmunds, with its entrance off the A1088 Elmswell to Ixworth road. The parish was once a series of separate farms that have been joined together by more recent development to form the present village centre. The Hall had been the manor house for the sub-manor of Little Haugh and sits beside the Black Bourne, a tributary of the Little Ouse River. It is situated in the hamlet of Stanton Street to the north of the village centre and north-west of the Church of St Andrew (Grade II), itself set away from the main settlement. It was said that King Henry VIII had dug for gold in woods on the Little Haugh Estate, albeit in vein. Parallel to the Bury Road, there is sandy soil in a wood that has traditionally been pointed to as the site of these mines where earthwork spoils were still visible until recently.

OWNERS OF LITTLE HAUGH HALL AND PARK

Once held by the Abbey of Ixworth, Little Haugh Hall was owned by the Ashfield family in the seventeenth century and acquired by Borowdale Mileson Esq. in 1641 and passed to the Mileson Edgar family. It was subsequently sold to Thomas Macro (d. 1737), a prosperous grocer in Bury St Edmunds who lived in Cupola House in the town. Whilst Thomas may have used Little Haugh Hall as a country retreat, it appears it was mainly intended as a house for his son the Revd Dr Cox Macro (1683–1767). Scholar, avid collector of antiquities, paintings and manuscripts and for a short period chaplain to George II, Cox was described as a ‘country gentleman of easy but not affluent fortune’.

The estate passed to Cox’s daughter Mary, who married William Stainforth of Sheffield. He is marked on Hodskinson’s 1783 map as resident, although the property was called ‘Little Loe Hall’ and his name spelt ‘Stanniforth’. It was inherited by William’s brother Robert Stainforth, passing to his daughter Jane and through marriage to John Patterson of Norwich. Later sold to Robert Braddock of Bury St Edmunds, it passed to Henry Braddock (d. 1868), maltster and brewer in Bury St Edmunds, who is shown as the owner on the 1841 tithe apportionment. The census of 1841 states that Peter Huddlestone, a barrister, was residing at The Lodge in Norton, although the tithe apportionment of the same year records him as leasing the house and pleasure grounds, but not the rest of the estate, from Henry Braddock. Soon after he bought the whole Little Haugh Estate. On Peter’s death in 1875 it was left to his widow Elizabeth and on her death in 1905 it was with her trustees.

During the twentieth century Little Haugh Hall had a number of owners and the estate appears to have been broken up, probably c. 1947 when it was put up for sale. Banker Stephen Partridge-Hicks bought the house and 25.5ha (63a) of parkland in 1998, but not the surrounding farmland, c. 323ha (800a) of which he acquired over the following seven years to allow the creation of two airstrips and improve the game shooting. In 2020 Little Haugh Estate was once more for sale.

LITTLE HAUGH HALL

In the northern part of the estate, the Hall depicted in Peter Tillemans’ early-eighteenth century painting (undated but produced late 1710s/early 1720s) is possibly the substantial house owned by Borowdale Mileson in 1674 when it was taxed on sixteen hearths. Peter Tillemans was a painter from Antwerp who moved to England in 1708. He was a friend of Cox Macro and is said to have lived at Little Haugh for twenty years before he died there in 1734, being buried in nearby Stowlangtoft churchyard. Following his father’s acquisition of the estate, in 1715 Cox started to make substantial alterations to the house, adding sash windows and rendering elevations. It is possible he was responsible for reducing its height to two storeys when he added an elegant staircase, although the Historic England house listing suggests this was done in the early-nineteenth century. Cox Macro’s alterations continued for at least another fifteenth years. The interior had intricate carving and plasterwork, with paintings above doors and fireplaces by Tillemans. Writing in 1859, Samuel Tymms described Macro’s house as ‘one of the best specimens at that time of an embellished residence of a country gentleman…’, a statement that Pevsner obviously agreed with when he wrote that it was ‘the finest of that date in the county’. The painting of the house, a portrait of two of Cox Macro’s children in the garden and a number of Tillemans’ sporting paintings commissioned by Cox are now held by Norfolk Museums Service in Norwich.

It is believed that Peter Huddlestone made alterations to the house c. 1830. This was the period when Little Haugh Hall was owned by the Braddock family, so Peter would have been responsible for the alterations when he was leasing the property. The original date of the tithe apportionments was 1839, although they were finally signed off in 1841. They show Peter living at the Hall, although the census of 1841 records the Huddlestone family at The Lodge in Norton. This suggests they may have moved out of the Hall during 1841 to a property nearby while work was done on the house. Peter went on to buy the whole estate and made further alterations c. 1850, including the addition of a northern service wing, now a separate cottage. His elegant house had an east-facing entrance front with fashionable white stucco wall and brick-faced south and west garden elevations with views across the parkland and gardens, although he left much of the interior unchanged. In recent years the house has been refurbished, reconfigured with the facilities upgraded and the eighteenth century interior restored.

THE PARK AND GARDENS

Peter Tillemans’ painting depicts the house and its surroundings as they were before Cox Macro began to make his alterations. It shows the east-facing entrance front of the house on rising ground with farm buildings to the north. A garden enclosure, inside which is a dove house, is shown within a moat in front of the house, which is likely to have been a seventeenth century moated orchard. The surviving sixteenth or early-seventeenth century bridge (Grade II) is shown crossing the Black Bourne with a tree-lined drive running east to west towards the house. The bridge was built of narrow red bricks with parts renewed using gault bricks in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. People are shown standing on a raised walk between the moat and the river.

Cox Macro started to develop his park and pleasure gardens around the same time he began the alterations to his house in 1715, the year his father wrote that his son made ‘alterations in the garden having sent down an abundance of Greenes’, meaning evergreens. Another painting by Tillemans dated 1733 shows two of Cox’s children in the gardens of Little Haugh within a grove full of trees, thickets and bushes with formal clipped hedges and a classically-styled summerhouse in the background. Perhaps the hedges are the result of the evergreens sent to Cox in 1715?

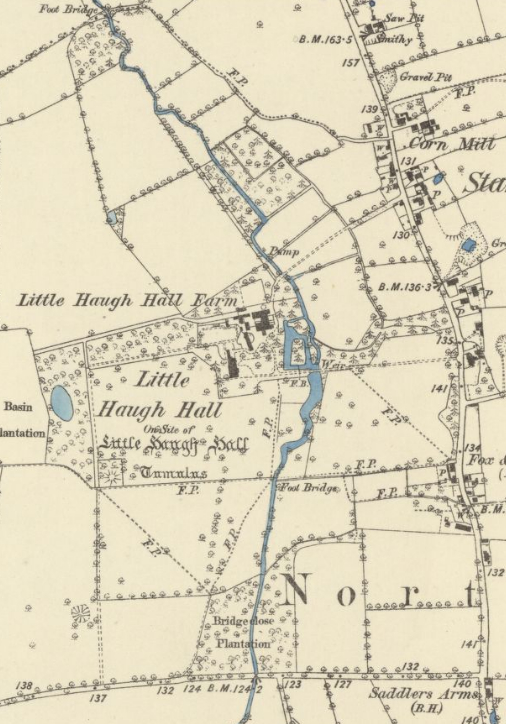

The first known full depiction of the Little Haugh Estate is the tithe map, drawn in 1840 to accompany the 1841 tithe apportionment. This shows the Black Bourne meandering through the park, bridged for the entrance drive from the east that led to the house and pleasure gardens, with a shelterbelt of trees flanking the eastern entrance drive. Between the house and the Black Bourne there was a moated garden, accessed from the house by paths that passed through plantings. By this time the dovecote shown in Tillemans’ painting had gone, with a field to the east named ‘Little dove house meadow’ on the tithe apportionment. To the north of the house ‘Great dove house meadow’ is shown with a small building in the western corner that was probably another dovecote. Between the meadow and the Hall there were stables, a farmhouse and irregularly-shaped area called ‘Garden’ on the apportionment that butted-up to the north elevation of the house. Although not made clear on the map, the position and shape of this garden correspond to the existing north and part of the west wall of today’s walled garden. A tree-lined walkway on the central axis of this garden, known as the lime avenue walk today, led west to a small irregular lake within an L-shaped wood known as Basin Plantation, where low-lying earthworks survive that probably represent paths and possibly sites of garden structures. A circular feature at its southern end represents a partly-tree-covered large mount for viewing the garden, often incorrectly thought to be a burial mound. Rubble and brick excavated from the top of the mound suggest it once had a small building on it, a summerhouse or perhaps a gazebo, and it seems likely this was an eighteenth century feature created by Cox Macro. By this time the farmhouse shown in Tillemans’ painting to the south of the Hall had gone. Further south a wood known as Bridgeclose Plantation is shown on the map with the river flowing through it, its western edge flanked by a track off the road leading westward towards Thurston. The track ran northward through the park, where it was partly-lined with trees, towards the Hall. This may represent an earlier main entrance to the site or perhaps just serving the lost farmhouse.

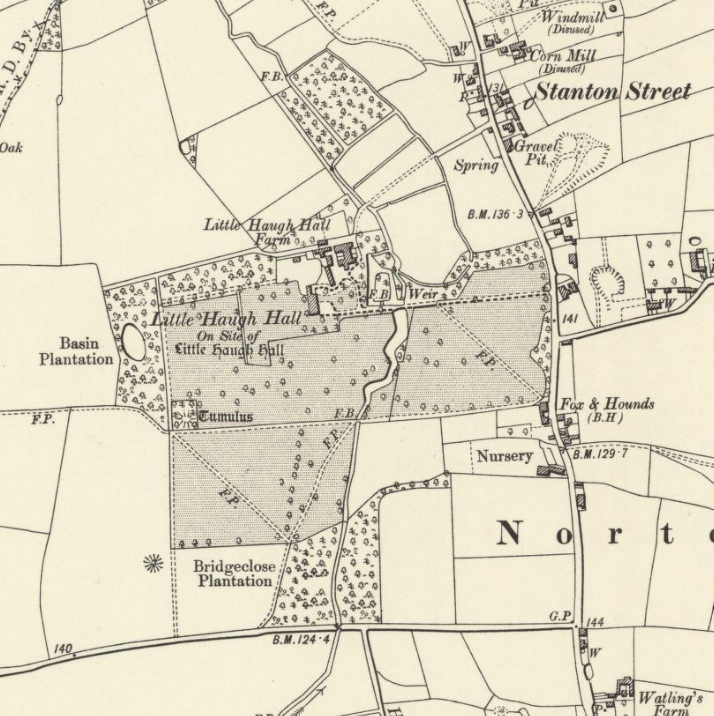

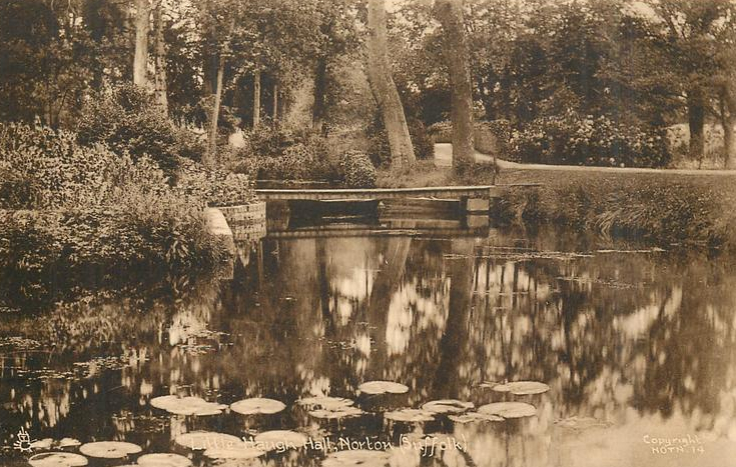

Probably part of the alterations made by Peter Huddlestone c. 1850, by the time of the 1884 OS map the meandering river had been widened to the south of the moat to create a thin serpentine lake flanked by parkland on either side. The map shows footpaths crossing the parkland – those running east to west and joined at the river by the earlier track from the south survive as public footpaths today. Slight changes had also been made to the farmyard buildings. Part of the irregularly-shaped garden in this area was lost when the service wing, now a separate cottage, was added to the house. This left the northern half intact with a perimeter path with the lime walk running westward now joining this part of the garden at its south-west corner rather than on its central axis as before. By this time a glasshouse had been added to the south-facing side of the north wall. Part of the original southern area of garden was now incorporated into the pleasure gardens and the rest accessed from the northern wing and enclosed by a curving structure – possibly a new wall – resulting in an L-shaped kitchen garden, fully enclosed by 1905, that was also accessed from the farmhouse. By 1885, south of the house a ha-ha had been created to separate the gardens from the parkland beyond, which had expanded westward by 1905.

When the Little Haugh Estate was put up for sale in 1947 the sales particulars refer to the south and west fronts of the house having attractive terraced lawns flanked by flower borders, clipped yews, copper beech and other trees, with flower borders, flowering shrubs and fir trees standing on the Island Garden that was once the moat garden. The walled kitchen garden was fully stocked with vegetables, wall and soft fruits and had three glasshouses plus a heated frame.

In 2020 Little Haugh Hall was once more for sale, at which time there were c. 24ha (60a) of parkland, gardens, lake and woodland, with an area of conservation land with lakes, woodland and pasture on the north-east edge of the estate. A number of mature nineteenth century oaks, sycamores and copper beech survive and additional planting has taken place to the east and west, supplementing older trees. The moat survived into the mid-twentieth century but has since been partly in-filled, the moat site now covered by bushes. By this time, due to access issues the east entrance had been moved slightly to the south and new entrance gates erected. The drive now curves northward to join the original 400m (1,312ft) long entrance drive, its vista now extended westward through pleasure gardens and beyond to the pond and L-shaped wood with surviving viewing mount, now covered with trees. The ha-ha also survives separating the formal garden and terraced lawns from the parkland to the south where an early-twenty-first century classical summerhouse has been built as an eye catcher in the parkland. A swimming pool and tennis court have been built beside the small west lawn. To the north of the house is the 0.2ha (0.5a) walled garden, which has been extensively rebuilt and refurbished. Probably the oldest part of the walled garden is the short west wall of flint rubble with brick buttresses and half-round coping that curves down in height to a gateway for a path leading out into the western garden that is in the same position as the lime avenue walk shown on the tithe map. The red brick north wall is probably a survival from the early-nineteenth century or perhaps eighteenth century, that now has an attached modern glasshouse. The other walls are more recent and of various ages.

In October 2024 Historic England published a report on the park and gardens associated with a possible listing of Little Haugh Hall under the Historic Buildings and Ancient Monuments Act 1953 within the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens for its special historic interest, although the assessment was that the garden or other land currently does not meet the criteria for registration.

The report can be viewed at: https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=1492135&resourceID=7

SOURCES:

Barker, H. R., West Suffolk Illustrated, 1907.

Birch, Mel, Suffolk’s Ancient Sites Historic Places, 2004.

British Brick Society Information, No. 37, November 1985.

Copinger, W. A., The Manors of Suffolk: The Hundreds of Babergh and Blackbourne, Vol. 1, 1905.

Heritage and Settlement Sensitivity Assessment for Babergh and Mid Suffolk Districts, March 2018.

Martin, Edward, ‘The Discovery of Early Gardens in Suffolk’ in Pastime of Pleasure, 2000.

Pigot’s Directory for Norfolk and Suffolk, 1830.

Pevsner, Nikolaus and Radcliffe, Enid, The Buildings of England: Suffolk, 1975.

Scarfe, Norman, article in Country Life, June 5, 1958.

Strutt and Parker, Little Haugh Hall Sales Particulars, 2020.

Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, Excursions, Vol. XXXVIII, Part 3, 1995.

Tymms, Samuel, ‘Little Haugh Hall’, Norton in Suffolk Institute of History and Archaeology Vol. II, 1859.

Walford, Edward, County Families of the United Kingdom; or, Royal Manual of the Titled and Untitled Aristocracy of Great Britain and Ireland, 1864.

White, William, Directory of Suffolk, 1844.

https://www.shootinguk.co.uk/features/game-shooting-at-little-haugh-hall-suffolk-11972/ (accessed January 2025).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cox_Macro (accessed January 2025).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Tillemans (accessed February 2021).

http://www.stedmundsburychronicle.co.uk/maltsters/maltsters.htm (accessed January 2025).

https://www.countrylife.co.uk/property/a-home-with-the-finest-georgian-interior-in-suffolk-with-walled-garden-pool-and-its-own-air-strip-218608 (accessed November 2023).

Historic England report associated with a possible listing of Little Haugh Hall under the Historic Buildings and Ancient Monuments Act 1953 within the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens for its special historic interest https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=1492135&resourceID=7

Census: 1841, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1911.

1783 Hodskinson’s Map of Suffolk in 1783.

1841 (surveyed 1840) tithe map and apportionment.

1884 (surveyed 1883) OS map.

1905 (revised 1903) OS map.

1953 (revised 1950) OS map.

2025 Google aerial map (Imagery ©2025 Airbus, Maxar Technologies, Map data © 2025).

Heritage Assets:

Suffolk Historic Environment Record (SHER): NRN 001, NRN 010, NRN 011, NRN 012, NRN 016, NRN 051, NRN 067

Little Haugh Hall (Grade II), Historic England No. 1352425. Church of St Andrew (Grade II), Historic England No. 1352425.

Bridge carrying driveway over the Black Bourn, 120m east of Little Haugh House (Grade II), Historic England No. 1032417.

English Heritage Assessment of Little Haugh Park for Registration of Historic Parks and Gardens. Reference No: 1492135. Unsuccessful and does not meet criteria for registration. Decision date 17 October 2024.

Suffolk Record Office (now Suffolk Archives):

SRO (The Hold, Ipswich) HD2833/1/SC304/1, Little Haugh Estate, Sales Particulars, 24 September 1947.

Site ownership: Private

Study written: January 2025

Type of Study: Desktop

Written by: Tina Ranft

Amended: